Chus Gutiérrez takes risks and makes bold artistic decisions in El Calentito, and the film works, I believe, because she incontrovertibly brings a woman’s sensibility to the film’s complex subject matter. But more than this, the film succeeds (I believe) because Gutiérrez is (1) a skilled filmmaker and (2) trusts her vision (like Buñuel in Los olvidados). It is disingenuous on my part to ask how the same film would be received if the director had been a man. Art doesn’t work that way. Only Picasso could create a work like Guernica, and only Chus Gutiérrez could create a work like El Calentito. Films succeed when their creators enjoy creative freedom and have unyielding faith in their artistic vision. Perhaps Antonia functions as a metaphor for the rule of artistic autonomy in her steadfast commitment to her personal autonomy.

I have used this film in my course on Spanish culture, and one of the factors that I considered before assigning it was that the director was a woman. The final scene of the film, when the protagonists take off their shirts and we see the word libertad spelled out on their backs, registers for me as an affirmation of female empowerment only because the director is a woman. Moreover, the moment when the father intervenes in defense of his daughter, resolutely opening the door and afterwards dressing down his wife, validates patriarchy too forcefully for me to be moved by it if the director had been a man. Finally, casting the mother as the engine of patriarchal authority (as in Like Water for Chocolate) recalls Lorca’s theatrical production, La casa de Bernarda Alba (1936), but registers as all the more impactful, in my opinion, by virtue of the director being a woman. Her decision to ascribe to the mother a patriarchal persona has a historical precedent, too, in the regime’s Sección Femenina. What I mean to assert, therefore, is that it is inevitable that the identity of the director will inform –implicitly or explicitly– our reading of a particular film. From a Film Studies standpoint, our goal is to try to recognize the ways in which our immediate reaction to a specific film might be influenced (positively or negatively) by what we perceive or know to be the subject position of the director before we sit down to do the work crafting a balanced and informed assessment of it.

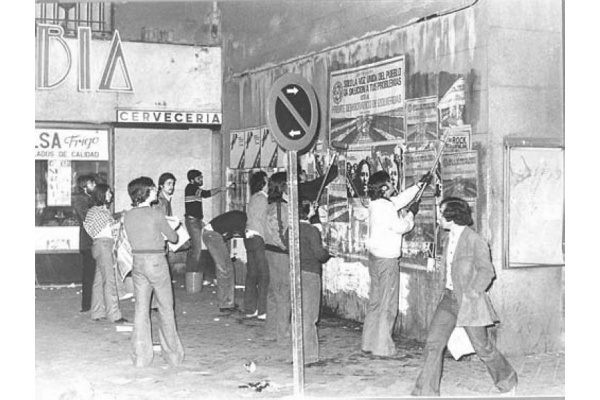

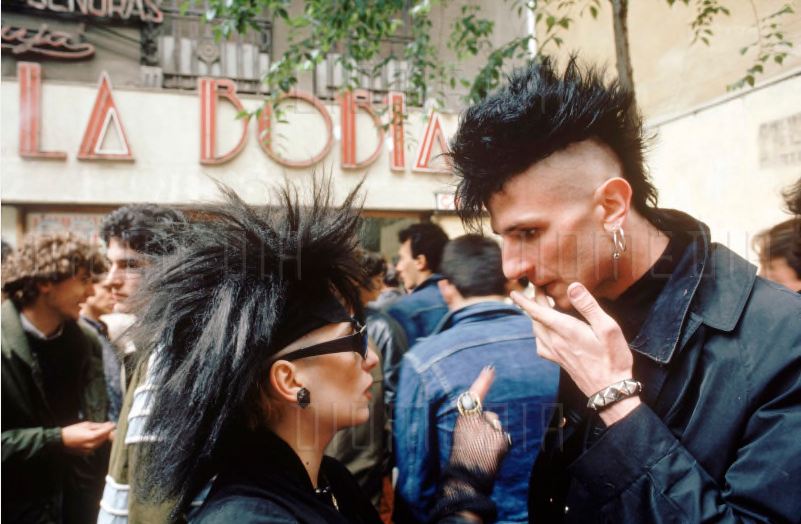

Incidentally, the bar in the film, El Calentito, is likely based on a bar in Madrid that was called La Bobia and was a nucleus of dissident activity during the regime and a magnet of the counterculture during the Transition and early 80s. Pedro Almodóvar was a regular and used it in a few of his early films. Curiously, the bar became Caftería Wooster in 1991. In 2015, the name was changed back to La Bobia. See photos below.

Leave a Reply