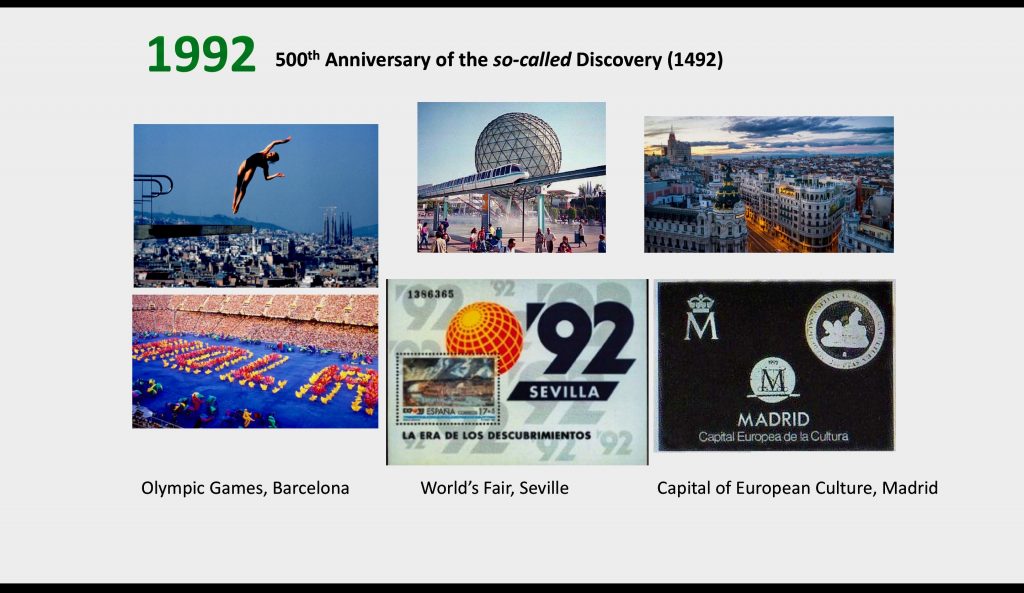

In 1992, Spain hosted the Olympics and the World’s Fair and Madrid was named European Capital of Culture. It is no a coincidence that these events coincided with the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage. In 1987, the name of the holiday commemorating the “Discovery” changed to El Día de la Fiesta Nacional. The new name conjures no direct association to the “Discovery,” but as I found out recently, the legislation that established it recognizes the day’s historical symbolism, asserting that the holiday commemorates the beginning of “a period of linguistic and cultural projection beyond the borders of Europe” (BOE).

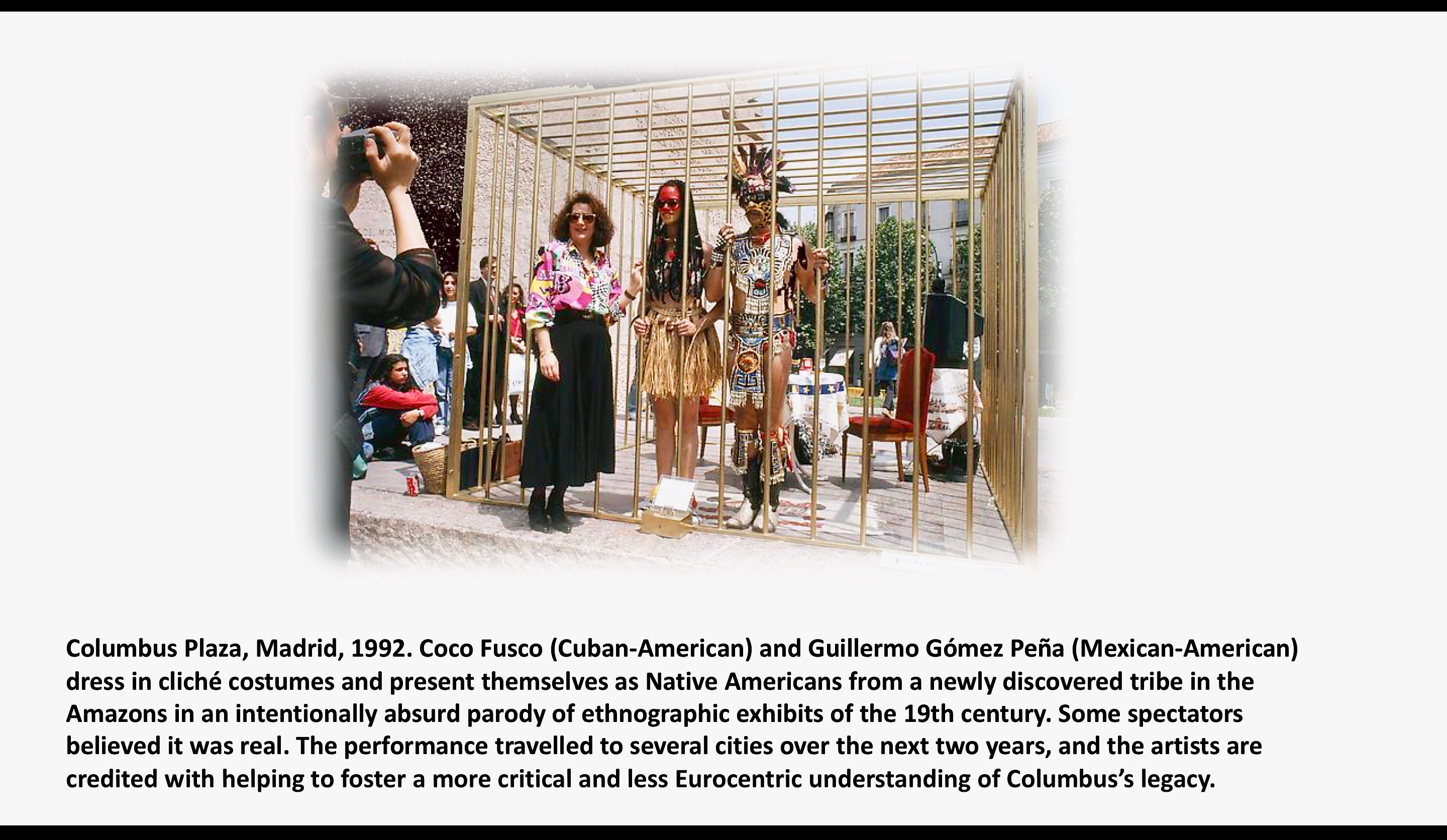

The performance by Coco Fusco and Gómez Peña attests to the impact that postmodern stagings of the absurd can produce. Some of the postmodern films that we watched take us into the realm of the absurd, which has a strong precedent, as we know, in Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou. Absurdity confuses audiences, but it also stimulates thought and disrupts our comfortable and uncritical understanding of the world. Films like Madeinusa, Matando Cabos, and Sexo por compasión are easy to dismiss or misinterpret if we don’t recognize an invitation in their absurdity to think more carefully about the themes that they explore (i.e. the postcolonial present; situational power; self determination).

Sexo por compasión drafts “a new cultural topography” that culminates in the community coming together and agreeing on a new set of rules that attest to their newly found devotion to egalitarian principles. The ironic salvation of the priest seems to infer that this renewed utopian society will continue to reserve a role for religion, and Padre Anselmo’s affirmative answer to the question of whether jealousy is a sin suggests that the town recognizes the continued need for an objective authority on human error. Conversely, when Manolo returns and discovers that Dolores/Lolita had slept with several other men in the village, he gathers them and corrects their perception of her (from that of compassionate caregiver to whore) in an aggressive and regressive renewal of patriarchal logic. This low point in the film exposes how the ways in which we accept the prejudicial conceptualization of certain behaviors condemns us to live in a black-and-white world that diminishes everyone. Gómez Peña affirms in the above passage that the language that we use on a daily basis contains ideological implications and (in)visible biases. Sexo por compasión explores this universal phenomenon in the figure of Dolores (saint)/Lola (whore). But let’s continue to explore this phenomenon, now, looking at Columbus Day from another angle. Commemorations in Latin America date back to the 1920s; surprisingly, only in the early 2000s did the objective of these national holidays begin to change to honor Indigenous communities (See Día de la Raza → por países). Similarly, a movement in the US to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day in lieu of Columbus Day took root in the 1970s and only recently has begun to grow in popularity. Change happens when progressive-minded people from across diverse segments of the population come together to pursue a common goal. Opposition is invariably strong even for the most righteous of causes, as the strange case of Columbus Day demonstrates in Spain, the US, and Latin America. My recommendation to anyone who feels passionately about a particular cause is to look for partnerships wherever you can, seek common ground, and befriend like-minded people.

The presence of each of you in the class attests to the validity of Gómez Peña’s assertion from 1989. Your commitment to doing the work for this course, however, is perhaps the most forceful testament to its validity.

Madeinusa broached the theme of American imperialism. Spanish-language cinema, as stated in the syllabus, enjoys only a small share of its domestic market in Latin America and Spain. Transnational productions have emerged as a strategy to compete with Hollywood cinema and increase the viewership of Spanish-language cinema (as Alberto’s research presentation explained). The above comment by Gómez Peña makes me think about the way in which south means other for so many people in the US, whereas north means familiar for so many people in Latin America. The films that we have seen in the course certainly draw from autochthonous cultural referents (i.e. Lucha libre, intrahistoria) but also European and US referents (i.e. Italian neorealism, French surrealism, and Hollywood). This aesthetic hybridity lends the cinemas of Spain and Latin America, in my opinion, a distinguishing quality.

I included A Better Life and My Family because these films are pioneering in how they bring the socially conscious style of Latin American cinema to Hollywood (literally these films are set in LA). Both exhibit the common traits of Italian neorealism, and both challenge audiences to reflect on pressing social issues (i.e. immigration, inequality, marginalization, systemic racism). My hope was that these films would help you appreciate the emotional impact that films like Machuca, La teta asustada, La historia oficial or El laberinto del Fauno undoubtedly had on their domestic audiences. It was gratifying to see your serious engagement with these films as US examples of the cinematic tradition(s) that have occupied our attention. The US has a higher Spanish-speaking population than several Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America (40 million), and therefore films that explore the realities that are specific to the Spanish-speaking communities here should naturally have a place in this course. I especially enjoy watching these films because they have a here-and-now quality that, at least for me, the others don’t have.

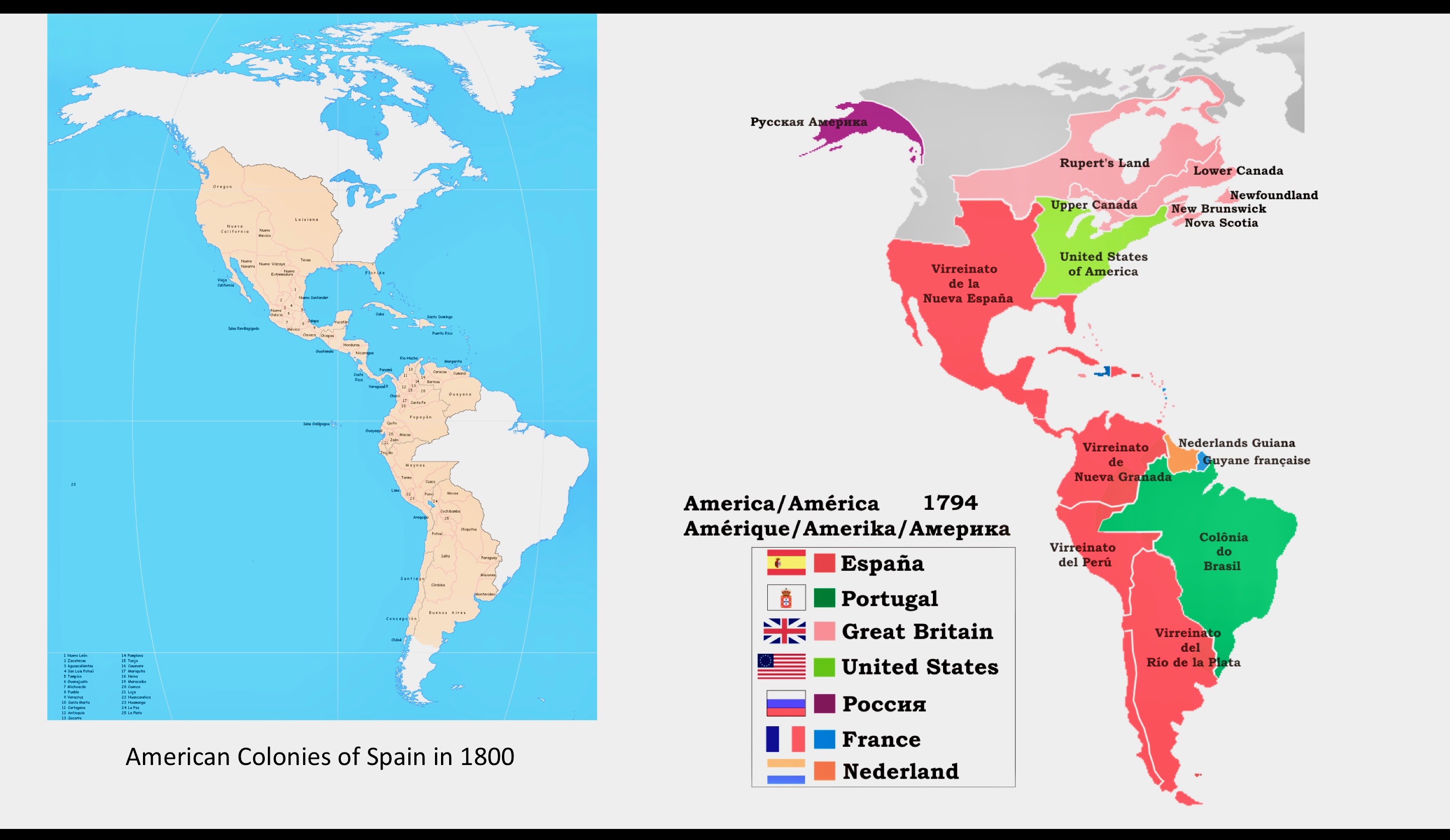

The map on the left shows Spain’s colonial possessions ten years prior to the historical events that would lead to Spain losing all but Puerto Rico and Cuba. The map on the right shows Europe’s colonial possessions around the same time. Colonialism throughout the Americas was predicated on racialized social hierarchies and was made possible by the exploitation of domestic Indigenous slave labor and imported African slave labor. The storylines of Machuca, También la lluvia and La teta asustada share a vision of contemporary Latin American society that has yet to reckon with its colonial past. As William Faulkner astutely wrote, “The past is never dead, it’s never even past.” If the themes that we encountered in some of the films are familiar, it might very well have something to do with our shared postcolonial condition.

Gómez Peña praises the reader for crossing a metaphorical border, and in so doing equates the act of acquiring new understanding with the physical act of crossing a border. By this logic, then, border crossing is synonymous with attaining enlightenment. This course has been about developing a threshold for crossing the imaginary border between our day-to-day reality and the invented reality of the film. Cinema has the capacity to enlighten those who possess the critical tools needed to understand complex films and those who, especially, exhibit a willingness to dwell on the border between realities at the risk of being transformed by the experience. The liberal arts, I might add, is a variation of what Gómez Peña postulates as border culture: It entails a willingness to step into the unknown in an effort to acquire knowledge and understanding, and it comes with the promise of transformation—no one leaves without having been changed by the experience. I was impressed by your willingness and effort to engage with the films on their terms. In so doing, you have exercised critical inquiry in a way that honors the liberal arts.

Finally, I want to encourage you to continue to cultivate an interest in Spanish and Latin American cinemas. Here is a list of recommendations. Most are the films researched by students for their final projects. Three are my recommendations:

El norte (1983, USA, Gregory Nava)

La vendedora de rosas (1998, Colombia, Víctor Gaviria)

El espinazo del Diablo (2001, Spain, Guillermo del Toro)

Soldados de Salamina (2003, Spain, David Trueba)

Cautiva (2003, Argentina, Gastón Birabén)

Diarios de motocicleta (2004, Argentina, Chile, Perú, Walter Salles)

La misma luna (2007, Mexico and USA, Alejandro Springal)

La montaña sagrada (2007, Mexico and USA, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

Sin nombre (2009, Honduras and USA, Cary Fukunaga)

Balada triste de trompeta (2010, Spain, Alex de la Iglesia)

Cinco de Mayo: La Batalla (2013, Mexico, Rafa Lara)

Relatos salvajes (2014, Argentina, Damián Szifron)

Magical Girl (2014, Spain, Carlos Vermut)

Una mujer fantástica (2017, Chile, Sebastián Lelio)

And if any wisdom was gained along the way, perhaps it was this: