Los olvidados is a film about Mexico City and the adverse social effects of poverty in an urban environment. The opening sequence situates the story as specific to Mexico City and also to other large cities in the West. Thus the themes that it explores are universal.

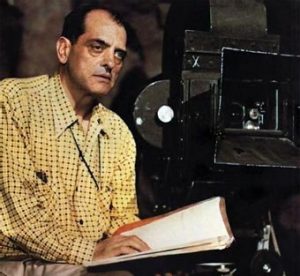

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) prompted migrations from Spain to all parts of Latin America, with a relatively large proportion of exiles opting for Mexico City. Buñuel left Spain in 1939 and worked for several years in Hollywood as a production assistant before emigrating to Mexico. At the time of Buñuel’s arrival in 1946, Mexico City was undergoing modernization and rapid population growth. It had a robust economy and a thriving film industry.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) prompted migrations from Spain to all parts of Latin America, with a relatively large proportion of exiles opting for Mexico City. Buñuel left Spain in 1939 and worked for several years in Hollywood as a production assistant before emigrating to Mexico. At the time of Buñuel’s arrival in 1946, Mexico City was undergoing modernization and rapid population growth. It had a robust economy and a thriving film industry.

Well before Buñuel arrived in Mexico City, he had gained international notoriety for his surrealist collaborations with Salvador Dalí (Un Chien Andalou and L’Age D’Or) and his parody of ethno-documentaries in Tierra sin pan (Land without bread, 1933). However, his career only began to flourish once he arrived in Mexico City, at the age of 46. Some but not all of the controversy surrounding Los olvidados had to do with Buñuel being an outsider, but it is unlikely that the film’s reception would have been different if a prominent Mexican director had made it.

Violence towards women is an especially noteworthy component of the thematic tapestry of Los olvidados. The viewer can infer that the reason that Pedro’s mother does not love him is because he was born as the result of rape, which occurred when she was 14, which is approximately the same age as Meche, who experiences unwanted sexual advances and assault (off camera). I can’t think of any film prior to Los olvidados that treats sexual assault so directly as a systemic social problem. On another note, El Jaibo reveals that he was an orphan and never knew his parents, and this lack of parental guidance potentially elicits sympathy from the viewer. This recalls the effect seen at the end of Bicycle Thieves when, as mentioned during class discussion, the viewer might be drawn to reflect on the circumstances of the thief who stole Antonio’s bike after seeing Antonio exhibit the same behavior out of necessity and desperation. With Jaibo, however, the revelation of being an orphan can also register as a convenient fabrication designed to manipulate Pedro’s mom. Jaibo’s supposed personal misfortune provides a seemingly logical explanation for his conduct, but this inference is not conclusive. The viewer’s subjective viewpoint, therefore, becomes a determining factor in making sense of Jaibo’s behavior from what seems to be a deliberate cloud of ambiguity that Buñuel creates around it.

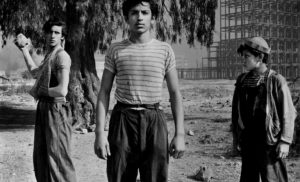

Buñuel could very easily have framed a story about Mexico City through the lens of Julián, who, when the story begins, had already extracted himself from the gang and had secured steady work in construction with the potential for advancement. We see him literally contributing to Mexico City’s modernization, which indeed brought jobs and shared prosperity. Julián has all of the elements needed for a heartwarming “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” story, but with his death at the hands of Jaibo, Buñuel deliberately eliminates this contrasting sub-narrative, and from here the dominant theme becomes marginalization and exploitation against a dystopian backdrop of economic stagnation (contrary to the reality of the late 40s). After Julián’s death, we never again see construction crews in action; rather, we see abandoned architectural shells in desolate surroundings, as in this scene where Jaibo scouts for a location to hide and runs into Ojitos.

Buñuel could very easily have framed a story about Mexico City through the lens of Julián, who, when the story begins, had already extracted himself from the gang and had secured steady work in construction with the potential for advancement. We see him literally contributing to Mexico City’s modernization, which indeed brought jobs and shared prosperity. Julián has all of the elements needed for a heartwarming “pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps” story, but with his death at the hands of Jaibo, Buñuel deliberately eliminates this contrasting sub-narrative, and from here the dominant theme becomes marginalization and exploitation against a dystopian backdrop of economic stagnation (contrary to the reality of the late 40s). After Julián’s death, we never again see construction crews in action; rather, we see abandoned architectural shells in desolate surroundings, as in this scene where Jaibo scouts for a location to hide and runs into Ojitos.

Buñuel’s portrayal of Mexico City’s poor and destitute is more pessimistic than De Sica’s portrayal of Rome and less pessimistic than Meirelles and Lund’s portrayal of Rio de Janeiro. Buñuel’s pessimism predates the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), which undoubtedly intensified his lack of faith in humanity and skepticism of the idea that human beings are naturally good. Here it is worth mentioning again the thematic parallels to Lord of the Flies (1954).

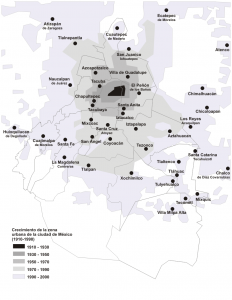

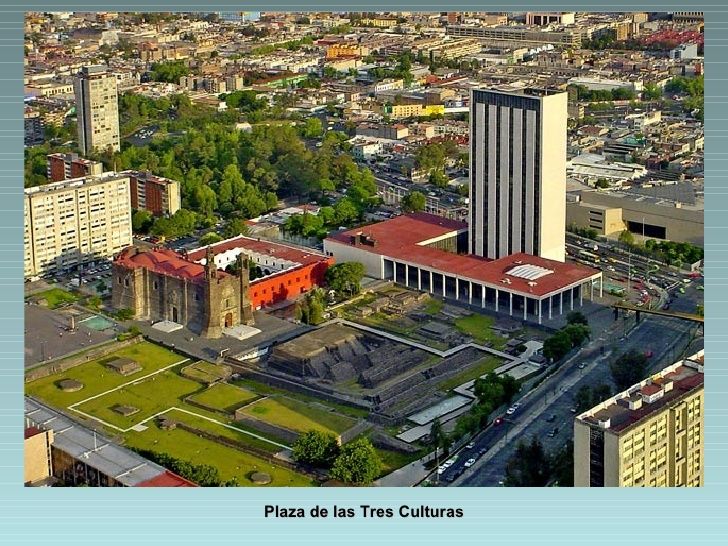

What motivated Buñuel to make Los olvidados? The most probable answer is that he was competing with De Sica and wanted to outdo Bicycle Thieves (Buñuel expresses admiration for Bicycle Thieves but disdain for neorealism in “Cinema, Instrument of Poetry” [1953]). It also seems likely that Buñuel’s Mexican collaborators wanted to bring the new aesthetic of neorealism to Mexico. Where we see the contribution of Buñuel’s director of cinematography, Gabriel Figueroa, for example, is in the selection of several geographical sites that have very weighty symbolism. The street where El Jaibo stops to buy a sandwich and where later Pedro is propositioned by an older man was known, informally, as Niños Perdidos (Lost Children, currently Avenida Lázaro Cárdenas); the gang’s rendezvous point in front of the church of Santa María de la Natividad Aztacalco had been

associated with crime since the eighteenth century (see La Romita); and moreover, the ramshackle dwellings where Pedro’s mom and Meche’s family live (Nonoalco-Tlatelolco) is where some of the displaced Aztec population found refuge after the conquest of Tenochtitlán (presently downtown) by Cortés in 1521. Furthermore, as noted in class, the reform school scenes were shot in a real reform school (Escuela Granja Tlalpan), and it is worth noting that Buñuel attempts to capture its progressive spirit in the character of the director, who enthusiastically describes the school’s pedagogical philosophy to his assistant. But Buñuel also portrays a regime of surveillance in the school, a theme that coincidentally appears in George Orwell’s 1984 (1949). It is as if Buñuel is suggesting that the school’s progressive vision of collectivism and self-policing (where everyone works and lives under the watchful eye of each another) is too suffocating for kids like Pedro who have been acculturated in an environment that sanctifies individualism and secrecy.

associated with crime since the eighteenth century (see La Romita); and moreover, the ramshackle dwellings where Pedro’s mom and Meche’s family live (Nonoalco-Tlatelolco) is where some of the displaced Aztec population found refuge after the conquest of Tenochtitlán (presently downtown) by Cortés in 1521. Furthermore, as noted in class, the reform school scenes were shot in a real reform school (Escuela Granja Tlalpan), and it is worth noting that Buñuel attempts to capture its progressive spirit in the character of the director, who enthusiastically describes the school’s pedagogical philosophy to his assistant. But Buñuel also portrays a regime of surveillance in the school, a theme that coincidentally appears in George Orwell’s 1984 (1949). It is as if Buñuel is suggesting that the school’s progressive vision of collectivism and self-policing (where everyone works and lives under the watchful eye of each another) is too suffocating for kids like Pedro who have been acculturated in an environment that sanctifies individualism and secrecy.

Los olvidados was pulled from cinemas in Mexico three days after its release due to public outrage. It is important to note that Hollywood films had often used Mexican actors as villains and rarely portrayed Mexico in a positive light (see “How Hollywood Has Portrayed Hispanics” [NYT, March 1, 1981]). Not only was Buñuel Spanish, but he came to Mexico via Hollywood, and Mexicans had a low tolerance for (a) Spaniards that they perceived as full of themselves and (b) for seeing their country portrayed as a land of criminals by outsiders. As mentioned in class, this criticism has limited validity given that Buñuel relied on a Mexican film crew that was as equally invested in the film as he was. Buñuel was also Catalán and brought with him a broad cultural perspective that might not have been as prevalent amongst exiles that arrived from other parts of Spain.

The inclusion of Los olvidados in the Cannes Film Festival prompted the Mexican government to register a formal complaint with the organizers. Mexico’s future Nobel Laureate, Octavio Paz, was deeply troubled by the government’s attempt to quash Los olvidados, which he viewed as an act of censorship, and as a result wrote an essay, titled “El Poeta Buñuel” (“Buñuel the Poet”), that he distributed to spectators as they entered the theater to view the film. Paz held a diplomatic post at the Mexican Embassy in Paris and was asked to attend the festival to promote Mexico’s official entry, Doña Diabla (directed by Tito Davidson), but instead exercised all of his influence to support Los olvidados. Paz’s essay was published shortly thereafter in a prominent Paris newspaper and picked up by international news services. In the essay, he defended the film on its artistic merits, and it is likely due to his intervention that Buñuel won the award for Best Director (De Sica’s Miracle in Milan took Best Picture). Paz’s essay contains an element of subterfuge in that it deliberately downplays the film’s realism and stresses Buñuel’s highly original poetic vision and tendency toward the subversive. Nonetheless, Paz takes an important stand in defense of artistic autonomy and against government meddling in the arts. Paz ostensibly saw the value of supporting someone like Buñuel who was willing to bring a vanguard modes of European cinema to Mexico, and in doing so, enhance Mexico’s already strong reputation for quality cinematic productions.

After its success at Cannes, Los olvidados was released in Mexico again and enjoyed a successful two-month run. Because of Paz’s intervention, Buñuel was able to entice Mexican investors to continue to support his work, and he would go on to make approximately 20 more films in Mexico over the next two decades. Buñuel’s willingness to make a film as provocative as Los olvidados is all the more extraordinary given his age at the time (49) and the fact that he had no more options if the film failed (Hollywood didn’t want him). Buñuel is a director remembered today for his steadfast faith in his artistic vision and promise (he never gave up on himself despite the setbacks he endured) and his uncompromising commitment to innovative cinematic productions in Spanish and French. His legacy of innovation and originality lives on in the work of contemporary Mexican directors Guillermo del Toro and Alejandro González Iñárritu.

A Dutch journalist living in Mexico City recently spent 56 days walking the periphery of Mexico City (pop. 21 million) photographing the landscapes and the lives of the people he encountered. The project can be understood as something like a postscript to Los olvidados. With each phase of the city’s expansion, the poor continue to get pushed to the margins where access to basic resources and transportation are limited. As mentioned by one student in class, this phenomenon can be seen throughout Latin America, where the chasm between the economically advantaged and the economically disadvantaged is vast.

In class on Wednesday, January 24, we compared the ending of one of the first Italian neorealist films, Rome, Open City (1946), to the ending of Los olvidados, exploring how these final shots convey optimism (Rossellini) or pessimism (Buñuel).

We also examined this brilliant still-shot from Bicycle Thieves. What story does the visual language tell?

Tangential Trivia: The Oscar statuette is thought to be a rendition of Emilio “El Indio” Fernández, who acted in Hollywood during the silent era and later went on to become a prominent director in Mexico. Read about this fascinating history of Emilio Fernández as the inspiration for the Oscar statuette here.

Sources

Rogers, V. Daniel. “Luis Buñuel’s Fictional Geographies.” Mapping the Megalopolis: Order and Disorder in Mexico City. Ed. Glen David Kuecker and Alejandro Puga. New York: Lexington Books, 2018. 41-64.

Sheridan, Guillermo. “Recordando Los olvidados.” Letras libres. (7 agosto 2013)

Leave a Reply